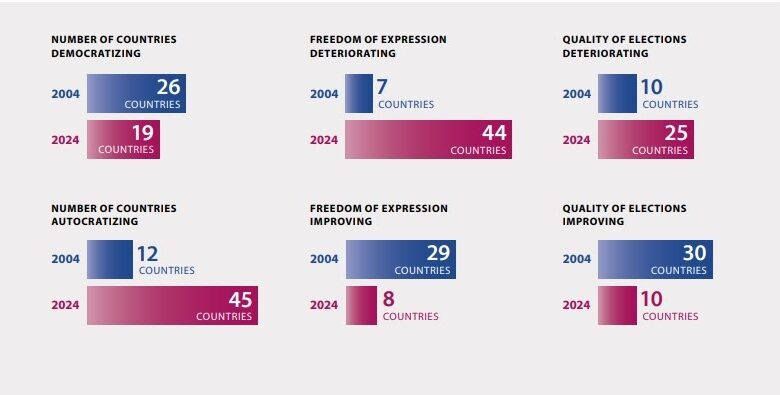

From 2025

V-DEM report

In global terms

autocracies are on the rise, and democracies are declining. According

to the V-Dem

Institute, for the first time in more than 20 years,

the world has fewer

democracies than autocracies. Other

estimates point to the same trend. At a global level

there are obviously many reasons why this is happening, but in

Western countries one stands out: the rise of right wing populism.

In many of the major

economies, the main political divide is increasingly between one or

more right wing populist parties and more mainstream parties of the

centre or left. Of course from year to year political popularity can

be volatile, but the trend is also unmistakable. This

is happening either because of the growing popularity of an insurgent

populist party (Rassemblement National and Reconquête in France, AFD

in Germany, Fratelli d’Italia in Italy and Reform in the UK) or the

transition of a mainstream party of the right into a populist party

(the Republican party in the US and the Conservatives in the UK).

Of course democracy

can survive the election of a right wing populist party into

government. There are plenty of examples of where it has (Trump’s

first term as POTUS, Poland and the UK, for example). But the nature

of right wing populism also means that there is a significant chance

it may not. Populism is about a political party proclaiming that it

alone represents ‘the people’, and that other parties or

institutions represent ‘elites’ that work against the people. As

a result, populist right wing governments tend to dismantle the key

elements of a pluralistic democracy, such as an independent media,

judiciary and civil service. They are autocratic, usually placing an

unprecedented amount of power in one individual’s hands. In those

circumstances, elections can easily cease to be fair, such that a

democracy is effectively replaced with an autocracy.

If the key electoral

contest in most major countries is between right wing populism and

more mainstream parties, then right wing populists are likely to win

at least some of these contests. If that sometimes leads to the end

of democracy, or steadily erodes the possibility of fair elections,

then unless autocracies collapse into democracies at an equal rate

the number of democracies will steadily decline and the number of

autocratic governments will increase. This process will be

accelerated if autocracies intervene in other democracies to support

right wing populism, as Russia has been doing and as Trump has

started to do.

Why are right wing

populist parties growing in popularity? This is an issue that I have

discussed many times, most recently here.

I think it is helpful to make a distinction between what some (not

just economists) describe as the demand and supply sides. The supply

side relates to politicians, the media and money: why for example

mainstream politicians may choose to adopt populist policies, or why

billionaires may fund populist politicians or parties. In the past I

have talked about why right wing parties wanting to push unpopular

neoliberal ideas might choose to focus on more social issues like

immigration. The demand side is about why right wing populism is

increasingly attractive to some voters. It is the latter I want to

focus on in this post.

It is familiar

territory that the politics of class, that used to be the central

divide in most major economies, has and perhaps still is being

gradually replaced by divisions between social liberals and social

conservatives. Of course economic issues remain very important in

elections, but increasingly the settled patterns in voting behaviour

are not related to class but rather to age and education. Socially

conservative voters tend to be older, and socially liberal voters are

more likely to have been to university. A central issue that divides

liberals from conservatives and which is becoming more and more

important in elections is immigration.

To look at why this

is happening we can focus on either the declining importance of

class-based economic issues, or the growing importance of

predominantly social issues like immigration. On the first, the

decline in manufacturing employment in most major economies and its

replacement by service sector jobs is part of the story. [1] This is

one reason for the declining influence of trade unions. In the UK I

think the triumph of Thatcherism and the end of incomes policies was

more important. You can also add into the mix the decline in the

Soviet Union as an alternative to capitalism.

Immigration has

become more important as an issue in part because there is more of

it. Immigration has

been on the rise in all regions, and pretty well all

countries within any region. However it is far too crude to suggest

that higher numbers automatically generate higher concern. Worries

about immigration are often greatest in areas where immigration is

relatively low and vice versa: London relative to other areas in the

UK is an

obvious example. A much more important determinant of

attitudes to immigration is where people are situated on the social

liberalism/conservatism spectrum (e.g. here).

Key determinants of

where people are on this spectrum are age and education. Two general

trends in most societies have amplified these divisions. First, over

the last fifty years more people have received a university

education, and this

increases the extent of socially liberal views. As graduates tend to form most of the political and broadcast media elites, this

may be one reason why social attitudes have become increasingly

liberal in most countries since WWII, although with the rise in right

wing populism this trend may be ending or even reversing. .

Second, the number

of older people has been steadily rising because of medical and other

advances. A crude measure of this is the old age dependency ratio,

which divides the number of people 65 or older by the number of

people of roughly working age (20-64). In 1960, the dependency

ratio for the OECD as a whole was 16%, but by 2020 it

had doubled to 30%. By 2075 this ratio is expected to be nearly 60%.

This means that a growing proportion of voters are no longer in work,

so work-based economic issues will have less salience, although this

effect is moderated to a minor degree by any increases in the retirement

age. In addition, older people are more likely to vote. All this

creates a growing pool of socially conservative voters which

politicians can appeal to.

While these trends

may help explain the growing importance of social and cultural issues

in elections, we need an additional step to explain why political

parties that aim to attract socially conservative voters are also

likely to be populist and autocratic. Socially conservative views

tend to go with authoritarian opinions:

social scientists often refer to the social conservative/liberal axis

as the authoritarian/liberal axis. Authoritarian views will generate

an impatience with independent sources of power (or

indeed democracy itself).

It also means that socially conservative voters are more likely to be

attracted by ‘strong’ (charismatic) leaders, of a type that generally lead populist parties.

All

this is a very broad brush account, and please tell me of any

important demand side factors I have ignored. But to

the extent that it is valid, it suggests that the factors that have created a growing demand for socially conservative populism, and further down the line the trend away from democracy, are unlikely to be reversed anytime soon.

[1] An alternative

story about the rise in populism focuses on those ‘left behind’

by this and other aspects of globalisation. This economic mechanism

appears very different from the social/cultural discussion that I

focus on. These two alternative perspectives regularly compete when

right wing populism triumphs. When Trump was first elected, for

example, there was plenty of debate between those who wanted to

essentially blame racist attitudes among the white majority and those

who wanted to look at the left behind in once prosperous industrial

states. Brexit saw similar discussions. Exactly the same tension can

be seen in

discussions about Poland’s recent presidential

election.

I have taken a

similar line to Dani

Rodrick on this, which is that this tension can be at

least partially resolved by distinguishing between levels and

changes. Social/cultural issues provide the bedrock of support for

right wing populists, but it is often economic issues that can tip

the balance between these populists winning or losing electoral

races. As this post is about the steady rise in right wing populism,

rather than why right wing populists sometimes win, I naturally focus

on social/cultural explanations.

Source link