.

Jagjit

Chadha (ex head of NIESR and now a Professor at Cambridge) and

Issam

Samiri have an article

in the Journal of Economic Surveys that focuses on the

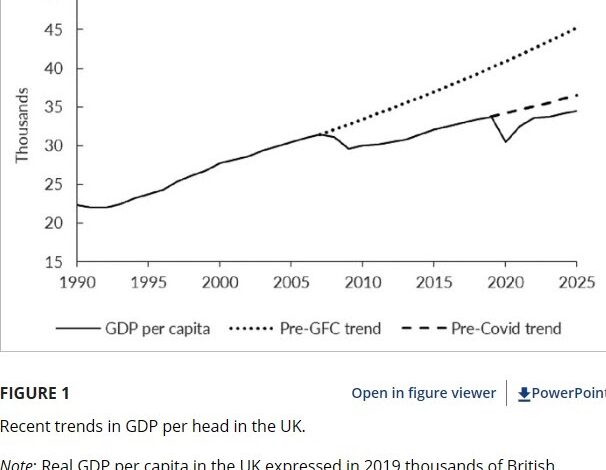

UK’s recent productivity problem. The chart above is taken from

that article. Economic growth (or not), and therefore how fast living

standards rise (or don’t) is all about productivity growth over the

medium and long term. The UK’s problem is this. Productivity growth

slowed in all the advanced economies from around 2005 onwards, but it

declined by more in the UK, and that relative decline has continued

until today.

There is not much the UK can do to buck international trends in

productivity. There was no way UK GDP per head was going to continue

to grow at pre-2005 rates, so the chart above greatly exaggerates the

problem. The survey discusses potential reasons why global

productivity growth started slowing around 2005. One story is that

the earlier boost to productivity provided by IT in the 1990s started

to fizzle out, but to be honest we have more stories than clear

answers on this. However, between around 1980 and 2005 the UK kept

pace with the US, Germany and France on productivity growth, so there

was no UK productivity problem over that period. Those who say the UK

has always been in relative decline are just factually wrong.

So what caused the relative UK decline in productivity from around

2005 onwards? The paper goes through various different studies and

explanations, and I cannot repeat them all here. How much is due to

the importance of banking to the UK economy, so the Global Financial

Crisis had an outsize impact on UK productivity growth? Did slower

global growth have more of an impact on the UK than elsewhere? Coyle

and Mei in a 2023 paper in Economica found that the UK productivity

slowdown was largely driven by the manufacturing and information and

communication sectors.

Below, in another chart taken from the paper, is the UK’s

investment to GDP share relative to other major economies. Investment

doesn’t just provide capital that helps produce output, but it is

often how technical advances are embodied in production. [1]

.

In the

1960s UK investment was substantially lower than in the US, Germany

or France, but by the 1970s the UK was at least within touching

distance of these other countries. It may reasonably take some time

for higher investment rates to show up as higher productivity growth,

so perhaps the UK’s relatively good productivity performance

from around 1980 was the delayed response to this higher level of

investment. Equally, perhaps the decline in relative productivity

from around 2005 was due to the decline in the UK investment share

compared to these other countries from around 1995.

One idea I looked at in

a previous post was that austerity, by delaying the

UK’s economic recovery from the Global Financial Crisis, may have

had a permanent negative impact on productivity through lower

investment. I concluded that austerity, in creating an unusually

protracted recovery in aggregate demand from the GFC recession, did

have some negative impact on productivity growth and therefore a

persistent negative impact on output supply, but how large that

effect may have been is very difficult to quantify.

As the chart at the top of the page shows, we actually have two UK

productivity/growth problems: the one discussed above, and another

that is more recent. In the UK the pandemic appears to have been assciated with a

fall in productivity, and perhaps a subsequent growth rate that is

even slower than since the mid 2010s. Luckily that is easier to

explain, as we can see from the chart above. Whereas the investment

share in Germany, France and the US went on increasing through the

2010s, the UK share started declining around 2016. The reason is of

course Brexit, and lower investment isn’t the only reason that

Brexit would lead to lower productivity growth.

While Brexit was clearly an act of national self harm in terms of

productivity growth and therefore UK living standards, the reasons

for the UK’s relative decline in productivity growth from the

mid-2000s remains something of a mystery, with many potential stories

with little consensus about which if any are the more important. My

own instinct is that the UK’s low levels of investment compared to

other countries since the mid-1990s has to be a key part of any

explanation of relatively low productivity growth, but the reasons

for these low levels of investment in the UK also remain largely unexplained.

[1] The structural econometric macromodel I and others created

in the 1990s had a vintage production function, where technical

progress is embodied in new investment.

Source link