Most people would

agree that taxes, taken as a whole, should be progressive. When you

add up all the taxes that an individual pays, the percentage that tax

is of their income should be positively related to how their income

is relative to others. The poor should pay a lower percentage of

their income in tax than the rich. The political argument is

generally about how progressive taxes as a whole should be.

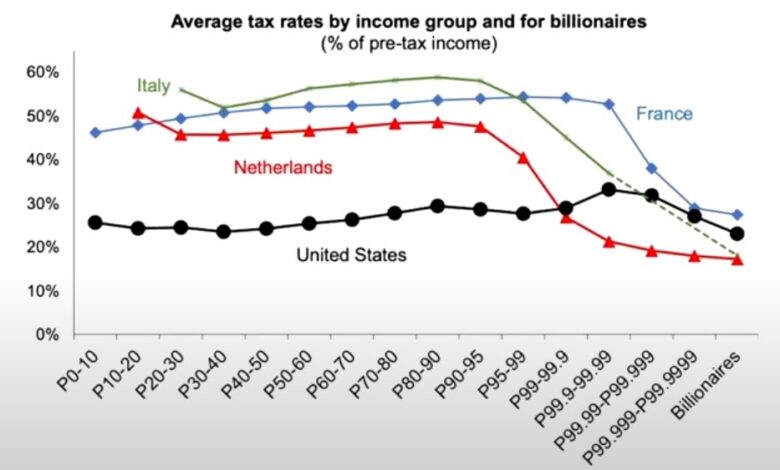

In most economies

taxes are roughly progressive until we reach very high incomes. The

chart below comes from a recentlecture by Gabriel Zucman.

In all four

countries taxes are mildly progressive (although the progression is

far from smooth) until we get to the very rich. Billionaires, in

particular, seem to pay significantly less in tax as a percentage of

their income than most other people.

This is hardly fair,

but it is perhaps not that surprising. Specifically much of the

income of the very wealthy comes from capital gains on the assets

they hold, and generally these will only be taxed when those assets

are sold. More generally those with a lot of money can afford to pay

people to help them avoid tax, and those with a great deal of money

have the power to influence whether politicians or those that collect

tax try to stop that avoidance.

One way to try and

rectify this unfairness, and also to raise a not insignificant amount

of revenue, is to try and change specific tax laws to prevent

avoidance or tax capital gains. While eminently sensible, this

approach suffers from two political problems. First, such proposals

are often highly technical, and so rarely attract widespread popular support.

Second, the very rich are also very skilled at finding individual

cases or circumstances where such changes in tax codes seem unfair.

Proposals for wealth

taxes, for example, are often countered by invoking the widow who

lives in a large expensive house but has relatively little income. There are ways

around such problems, like deferring tax, but as those that own the

media also tend to be very rich those work arounds can easily get

lost in public debate. Another example became apparent in the UK

recently, after the government changed the law to allow farmers to

pay some inheritance tax. It was quickly claimed that doing this

would prevent farmers passing on their farm to their children,

demonstrations were organised and newspapers campaigned, featuring

wealthy celebrities some of whom had bought farms just to avoid

inheritance tax.

An alternative

approach is to only look at the total taxes paid by the extremely

wealthy, and set some minimum level of their wealth that these

individuals should pay each year. If they already pay that minimum

then fine, but if they pay less than that minimum they will be

required to pay an additional tax to reach that minimum. This is the

idea pioneered by Gabriel Zucman, an economist at the Paris School of

Economics and former pupil of Thomas Piketty. [1] Specifically he

suggests billionaires, or those with wealth above 100 million, should

pay total taxes each year worth a minimum of 2% of their wealth.

The great advantage

of this approach is that it is harder to obstruct politically. As the

tax applies only to the extremely wealthy, it is much more difficult

to evoke public sympathy for any of the individuals involved. As the

wealth of the very rich can easily increase by more than 5% a year,

paying just 2% in tax will hardly cause hardship.

The breakthrough for

this proposal came at the G20 summit last year, when hosts Brazil

asked Zucman to present his proposal, and managed to get

countries to agree: “With full respect to tax

sovereignty, we will seek to engage cooperatively to ensure that

ultra-high-net-worth individuals are effectively taxed.” The

“Zucman tax” was

adopted by the French parliament (the far right

abstained), but was rejected

by the Senate.

A standard objection

to taxing the very wealthy is mobility. If you try to tax

billionaires more they will move to a country that taxes them less,

and you will lose all their tax. Again we saw an example of this in

the UK last year, with a report claiming a wealth exodus from the UK

caused by proposed tax changes. However the reality is rather

different to the rhetoric. In his detailed

proposal for the G20 Zucman notes that recent studies

suggest that such billionaire flight is modest, and that the number

of billionaires who live in a country different from their country of

citizenship is still below 10%. Last year’s UK study, although it

got widespread publicity at the time, was always of dubious status

and has since been debunked.

[2] To reduce even this modest possibility of billionaire flight,

countries could charge an exit tax, or could continue to tax

individuals wherever their companies do business.

Because Zucman’s

proposal sets a minimum tax of 2% of wealth, it is not in competition

with other proposals to change the tax system designed to make it

less regressive at the very top. In some ways it could be seen as a

means of making other measures easier to implement. For example, if

billionaires are paying a minimum tax anyway, proposals to reduce

forms of avoidance on other taxes will receive less opposition from

the very wealthy because any additional tax they will pay will just

mean they pay less to reach the 2% threshold.

Zucman’s proposal

is incredibly modest. It would just

stop the richest in society paying less tax as a proportion of their

income than everyone else. It is highly unlikely to stop the wealth

of the richest from increasing. Many would like to go further, but

the great advantage of his proposal is that it will be seen as fair

by virtually everyone. We know that monied interests have the power

to persuade governments that taxing them fairly will lead to all

kinds of imagined horrors, or to persuade politicians that taxing

them would not be in their personal interests. The French government

opposed the Zucman tax. The only realistic chance we have of taxing

the very rich fairly is to oppose such lobbying with mass support.

Only democratic pressure can fight a plutocracy.

[1] Something

similar was suggested by Warren Buffet more than ten years ago, when

he noted that his secretary worked just as hard as he did, but paid

twice as much of her income in taxes. His proposal was adopted

by President Obama, but was rejected by Congress.

[2] Arun Advani and

colleagues look at the impact of past changes in the taxation of

non-doms here.

Source link