VATICAN CITY (RNS) — More than 20 years ago, Steen Heidemann stumbled into Westminster Cathedral in London, where he was studying architecture, and witnessed his first Mass. Born to an atheist family in Denmark, Heidemann had previously only heard about Jesus in history books.

The spiritual experience was so strong he was struck to the ground, launching his journey of conversion to Catholicism. He moved to Normandy, in France, where he became acquainted with the Jesuit order, which he credits with understanding the “power of image.” To find his faith, Heidemann said, he had to know the face of Christ.

So began Heidemann’s dual quest — his professional one, traveling and collecting art for exhibits and museums from Helsinki to Zagreb. And his own spiritual one: over the next two decades, Heidemann searched for portraits of Jesus by living artists, eventually collecting 240 paintings by 40 artists.

In recent years, he has begun exhibiting this private collection in a show called “Faces of Christ,” and in May, the exhibition will find a semi-permanent home at the Toledo Cathedral in Spain, in the former apartments and cloister of Queen Isabela. The works by well-known contemporary artists, including Legrand, James Langley, Raúl Berzosa and Antonio Ciccone, will join the cathedral’s existing displays of masterpieces by El Greco, Raphael and Caravaggio.

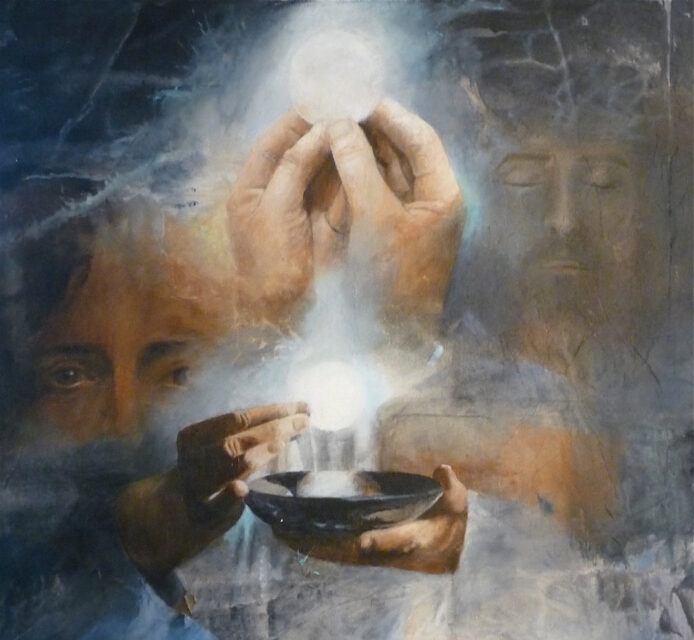

“The Eucharist I” by Hélène Legrand. (France) (2012)

Heidemann believes that, if the church were to draw closer to the arts, it would attract young people to the Catholic faith — just as it had happened to him. “It’s a little, first try to hopefully encourage the church to have a renaissance in art,” said Heidemann.

Steen Heidemann. (Courtesy photo)

The father of four also sees art as bypassing prejudice or ideology and appealing to the generation that has grown up amid a flood of imagery online. “For young people everything is mobile, everything is image,” he said. If they don’t like something, he adds, they just move on to the next thing.

The Catholic Church’s patronage of the arts gave birth to many of the religious masterpieces that are admired today, but Heidemann said that religion no longer motivates artists. He wants the church to encourage “in each area of the world the best artists to try and represent what they think in their culture.”

Heidemann’s collection includes works from a range of locations, from Tanzania (by Thobias Minzi) to Brazil (Sérgio Ferro), and he is confident that it will one day include many more. He would also like to add sculptures and architecture to the collection.

The exhibition is not a survey, but, the collector readily admits, a reflection of his own perspective as to what Catholic art should look like. The portraits evoke the Old Masters and avoid abstraction. “Christian art has always been figurative,” he said, “and I remind people that Christ’s message is so rich and so diversified that you need figurative art.”

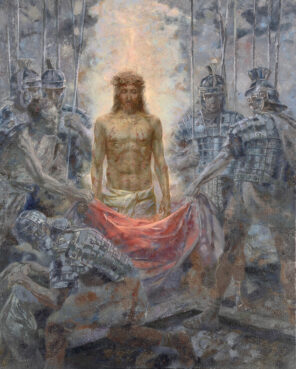

Finding such paintings was no easy task, he said. Religious artwork is rarely found in galleries of the art capitals of London, Paris and New York. Heidemann commissioned pieces from artists he admired, working closely with them to foster a new sensibility and perspective of religious themes. He asked some artists to recreate their interpretation of “The Disrobing of Christ,” a masterpiece by El Greco at the Toledo Cathedral, which resulted in innovative and striking renditions.

He found the other works in the atelier of artists who had made them because they were inspired to do so, either because of religious belief or sudden intuition, he said.

Some of the artwork in the collection will continue to be lent to other exhibitions around the globe, Heidemann said, to inspire interest in Catholic art and artists.

Source link