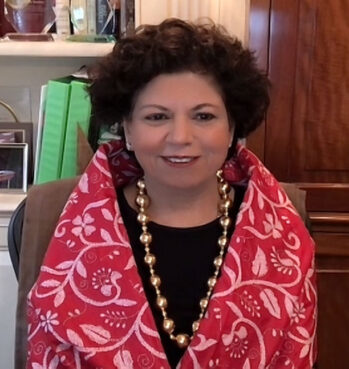

(RNS) — The winner of the 2025 Grammy Award for best new age, ambient or chant album — a category once dominated by Enya — was an album titled “Triveni,” meaning “the confluence of three rivers” in Sanskrit, an apt description for its weaving of Vedic chants, melodic flute and cello by India’s Chandrika Tandon, South Africa’s Wouter Kellerman and Japan’s Eru Matsumoto.

The name, which is given to the meeting point of the holy Ganges, Yamuna and Saraswati rivers, said singer Tandon, came to her in one of her daily meditations.

“It was a beautiful coincidence that our album called Triveni won the Grammy on Vasant Panchami when the Maha Prayag was going on,” Tandon told RNS, referring to the ongoing Maha Kumbh Mela festival held where the three rivers meet in Prayagraj, India, considered one of the holiest pilgrimage sites in the nation. The world’s largest gathering of humanity, with 400 million people attending this year, the Kumbh Mela happens every 12 years, with this year’s celebration, the Maha Kumbh Mela, happening only every 144 years, when the sun, the moon and Jupiter align.

“Think what you like, say what you like, but one has to just smile at this incredible coincidence,” Tandon said.

Tandon was a prominent business mogul for more than half her life, the namesake of New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering and sister to former PepsiCo CEO Indra Nooyi. Twenty-five years ago, however, Tandon faced what she describes as a “crisis of spirit.”

“I knew I had everything, and yet I felt like I had nothing,” she said. “If I died today, what is it that I want to have accomplished? Is it just more money, more climbing up the ladder, or was there something else that would just give me happiness and make each day complete?”

That something else, she found, was devotional music. Pulling from the mantras she once heard as a little girl in Chennai, Tandon found a new purpose in creating melodies and “praying into the notes” as a form of meditation. “Music helped me find myself,” said Tandon, the creator of six albums of her own.

And according to Tandon, the Grammy win signifies a larger cultural moment, helping young people all over the world discover the “extraordinary gems” of the ancient Vedic traditions. “Instead of a traditional Indian ornate piece of jewelry, I’ve simply put them in a completely Western jewelry setting,” said Tandon. “Suddenly it’s more apparent, it’s more discernible, more relatable. And suddenly there’s this curiosity about, ‘What is that? It makes me feel so good!’”

According to Tandon and other devotional musicians, the melodic repetition of Vedic mantras, often associated with the many names of the tradition’s various deities, has proved to calm the mind for centuries. The 21st is no different, they say, as they see a burgeoning space for the spiritually curious youth seeking a respite from the fast-paced internet culture they grew up in. Now, a new generation of kirtan artists is leading the charge on Hindu sacred music.

Amid confusing times, says devotional musician Gaura Vani, Generations Z and X have found a way to articulate their complicated emotions and feelings through the call-and-response style of kirtans, the devotional songs commonly associated with the Hare Krishna faith.

“This is almost a miraculous thing to say, but in this world of social media and phone addiction and all that, the kids in the Krishna community are doing the craziest thing: Without anyone telling them to, they will find a weekend where everyone’s free, they will dress to the nines together, and find a temple or a space where they will do kirtans for, like, 10 hours straight,” he told RNS. “It’s crazy. It makes no sense in the modern world, but they’re doing it.”

Vani, born into an American Hare Krishna family, just performed his first solo live concert at Mumbai’s Royal Opera House in late January. Once the head of the successful early 2000s “Krishna-conscious” rock band As Kindred Spirits, Vani joined musicians from the East and the West for a fusion of world music, mantra, pop and rock. “It’s all about spiritual stories and spiritual music from around the globe,” he said. “That’s kind of my jam.”

Some form of singing or chanting takes place in almost every Hindu tradition, says Vani, but the bhakti, or devotional, tradition practiced by members of the International Society of Krishna Consciousness, or ISKCON, places an emphasis on music as a way to connect with the Divine, and “as a way to create harmony, peace in the world, peace in oneself and to heal both spiritually and physically.”

The Maha Mantra, a repetition of the words “Hare,” or praise, “Krishna” and “Rama,” set to any melody the singer, or kirtaniya, chooses, is an ISKCON staple. This Sanskrit call-and-response, with the names of God sung alongside a harmonium and a mridanga, a type of drum, says Vani, can lead participants to a “flow state” where it may feel like “music is kind of descending from the heavens and coming out through you.”

“It’s the closest thing to ecstasy I’ve ever experienced,” said Vani.

Steeped in this tradition since birth, Vani and his wife, a trained Indian classical dancer, have now surrounded their three teenage children with song and dance. But as Vani has taught his kids, spiritual meaning is not limited to kirtans: “If you look for it, spiritual music is all around us, in all cultures,” he said, from gospel to Sufi Zikr to praise music from South Africa. And, says Vani, it’s in his daily playlist of Nora Jones, George Harrison, the Talking Heads and The Police. (The latter’s song “Spirits in the Material World” is, he said, a personal family favorite.)

Premanjali Dejager, a 24-year-old “Krishna kid” — a term of endearment for those raised in a Hare Krishna household — lives in New York’s Bhakti Center ashram and doesn’t go a day without chanting the Maha Mantra a few times. The kirtaniya, who grew up in Australia, says kirtans can feel like a “spiritual dance party,” where “teenage angst” and “club dance moves” meet in a safe, nondestructive environment.

“When you’re in the midst of it, like, when someone is really singing from their heart and, like, really connecting, you feel that sense of connection in the room,” Dejager, who grew up in Australia, told RNS. “It’s just contagious.”

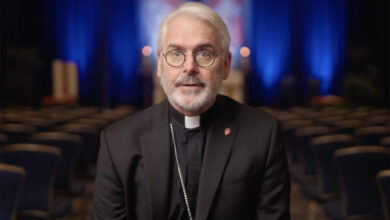

Dejager has sung around the world with her guru Indradyumna Swami, known as the Travellng Monk, since graduating gurukul, or “spiritual high school,” in 2018. But, she said, she wasn’t always so musically inclined. “I was actually a really terrible singer,” she said, recalling that she was removed from her primary school’s singing group because she “just couldn’t sing on key.”

Yet taking singing lessons in jazz and pop music grew Dejager’s confidence, and she started posting devotional singing videos on social media, some of them “really cringy.” Today, she has more than 50,000 Instagram followers and her own virtual kirtan school, where she has, since 2021, taught other aspiring singers over Zoom that what’s important is “being real,” or coming as you are to the devotional practice.

“Sometimes, if I’m feeling really sad or going through something difficult or having to make a difficult decision, that’s what’s on my mind,” she said. “It’ll just be a prayer offering of like, ‘Krishna, I need your help here. I need your guidance.’ And sometimes it does happen where I’m having to catch myself from like spacing out, and my mind goes everywhere. It is a practice of constantly trying to bring the mind back and just trying to bring my heart into the picture.”

Nikita Bhasin, a California native, considers herself more spiritual than religious. A certified yoga instructor since the age of 16, Bhasin was raised attending and singing devotionals at the Kali Mandir in Laguna Beach — a common story of being “dragged along by my family.”

“I left all the kirtan stuff behind because I was older and I didn’t have to do what my parents told me to do,” Bhasin, 27, told RNS.

But Bhasin eventually found her way back to the music, when she learned yoga from an instructor who began practice with the same chants she heard as a child, but in a “more digestible” 10-minute format rather than the three hours she spent at the temple. She took up the harmonium and now opens and closes each of her yoga classes in New York, barring if they are in a gym setting, with a Sanskrit chant, often to the theme of the asanas, or postures, such as repeating “Jai Ma,” or hail Mother Earth, in a class about “balancing opposition.”

Many of her students have never chanted before, holding varying beliefs (or no beliefs) about God, some coming only for the physical asanas of yoga. Bhasin invites them to “put their own spin” on the ancient practice.

“A lot of these chants, you are chanting to something higher than yourself,” she said. “And there’s a lot of interpretations of that. There’s thousands of lineages that think of God or divine as something different: Divine could be a hug from your friend, or it could be feeling like you’re not on autopilot and are grateful and connecting with people in your life.

“It’s been interesting, because a lot of people tell me after class that they haven’t sung since they were like 10 years old, and this is how they’re coming back to their body and coming back to this childlike spirit of just letting go,” she said.

Source link