Already bored

with the election? Here is a bit of economic history instead.

To many readers of

this blog, 1979-83 will seem like ancient history. To some of us, it

was part of our formative history as adults. I joined the Treasury as

an economist in 1974, straight after finishing my undergraduate

degree. At the time a career in public service rather than academia

via a PhD seemed much more interesting and useful. In 1979 the

Treasury generously sent me to do a masters degree, on the condition

that I worked at least another two years at HMT. While I was doing

the masters Mrs Thatcher was elected Prime Minister, and the Treasury

I came back to was a rather different place to the one I had left.

[1]

Tim Lankester became

a Treasury civil servant just one year earlier than me, after working

for the World Bank. His talents obviously shone, and he became

private secretary to Jim Callaghan in 1978, and then private

secretary for economic affairs to Mrs Thatcher in 1979. He therefore

had a particularly interesting vantage point in which to view the

brief but highly significant UK monetarist experiment. He went

on to have a very distinguished career as a civil servant (becoming

permanent secretary at the Overseas Development Administration) and

then in education. This helps explain why it took a pandemic and

associated lockdowns for him to get around to writing

about those events some fifty years earlier.

Being a civil

servant Lankester was no true believer in either Thatcher or

monetarism in 1979. Partly as a result his book, which relies on a

lot of very good research as well as personal memories, is a pretty

objective account of the monetarist period, as well as covering what

came before and ending almost at the present day. It is also very

well written and easily accessible to non-economists.

The book starts by

setting the scene in the summer 1981 with a cabinet meeting.

Unemployment has soared, firms are going bankrupt, inflation is still

high and money targets are being missed by miles. Minister after

minister asks Thatcher to change her economic course, and she is only

saved by Deputy PM William Whitelaw, who tells her restless cabinet

to give the policy more time. In reality it was near the end of what

Lankester calls ‘hard monetarism’.

The book also begins

on a more personal level with a London dinner party around the same time,

where Lankester is sitting next to Ben Bradlee, editor of the

Washington Post and famous for helping uncover Watergate. After

giving a standard defence of Conservative policy to a sceptical

Bradlee, a journalist opposite tells Bradlee very loudly that

Lankester is Thatcher’s Albert Speer. During a stunned silence

Bradlee whispers to Lankester “You either hit him or you have to

leave”, and he leaves. As Lankester walks home he wonders to what

extent he is complicit in Thatcher’s economic policies. He thinks

of Henry Neuberger (a good friend of mine) who left HMT to become an

advisor to Labour leader Michael Foot. I think it was Henry who wrote

that monetarism was like trying to control how much people ate by

regulating the supply of crockery. I too got out exactly when my two

years was up to work at the then fiercely anti-monetarist National

Institute. Not only did I think monetarism was foolish and dangerous

at the time, but I was also beginning to see the value in good

academic research. [2]

Of course the

monetarist policy failure had nothing to do with civil servants like

Lankester and everything to do with Mrs Thatcher and her Treasury

ministers. What I personally found most interesting from Lankester’s

account, perhaps because I experienced monetarism from a Treasury viewpoint,

was how much Thatcher herself was a dedicated monetarist. It is quite

fair to describe this episode as Thatcher’s monetarist experiment.

Part of the reason

Thatcher adopted monetarism, which was a distinctly minority view

among UK academics, was the failure of what went before: politicians

trying to override the Phillips curve by using Incomes Policy.

Lankester recounts a meeting between Callaghan and union leaders

months before he lost the election, when one union leader banged his

fist on the table and said “It’s your job, Jim, to get inflation

down to 2%; it’s my job to get 18% for my members”.

When Thatcher

defeated Heath to become Tory leader, she set up the Economic

Research Group (the first ERG!?) chaired by Howe. Although

politicians sympathetic to monetarism (including Lawson) were in a

majority, it didn’t help that those opposed advocated Incomes

Policy instead. But Lankester argues that “monetarism came

naturally to” Thatcher. The link between the money supply and

prices seemed obvious to her. Although she liked Freidman’s account

of monetarism as a ‘scientific doctrine’ akin to the law of

gravity, he suggests she was a monetarist by conviction. Lawson

called it ‘primitivist’ monetarism. For Thatcher monetarism just

had to be true. [3]

Lankester and

Thatcher’s views on both economics and society more generally were

quite different, but despite this they got on very well, I suspect in

part because Lankester was very good at knowing the limits of his

private secretary role. Thatcher made it clear that the only advice

she wanted from him was on points of interpretation and detail.

Lankester admired many of her personal qualities (e.g. her

self-belief, her drive and her personal integrity) as well as some of

her policy achievements, but he describes monetarism as her biggest

mistake. One of the downsides of self-belief is that you can imagine

that in areas where you have little knowledge your beliefs are

superior to the beliefs of the majority of experts

The mistaken basic

concepts of monetarism (the stock of money was a very poor indicator

of policy stance, and controlling an intermediate target was inferior

to controlling the policy objective) were compounded by tactical

errors by ministers. Chancellor Howe decided on a 7-11% target range for the money

supply, essentially because it was felt it had to be lower than the

8-12% adopted by the Labour government, even though for Labour these

targets were largely cosmetic. Yet wage pressure had increased, oil

prices were increasing, and the new government doubled VAT, which

meant that this target range was far too tight. Lankester suggests

that only Lawson understood this. Indeed he suggests Thatcher didn’t

understand the implications of such a tight target for interest

rates, which she hated to see going higher.

Interest rates went

higher and higher, yet money growth still exceeded its target. As an

anti-inflation policy it was a cold turkey strategy, not by design

but because the monetary target was sending completely the wrong

signals.

The famous 1981

budget was the last major act in the brief monetarist story, and

Lankester rightly describes its tax rises as a mistake because they

reduced the strength of the subsequent recovery. [4] The 1982 budget

raised the targets for monetary growth, as well as introducing

additional targets for different definitions of the money supply.

When Lawson became Chancellor, he in practice focused more on having

an exchange rate target, which he had argued for in the ERG as

preferable to money targets. That eventually led to a second major

macroeconomic blunder, but that is a different story (although it is

covered in this book).

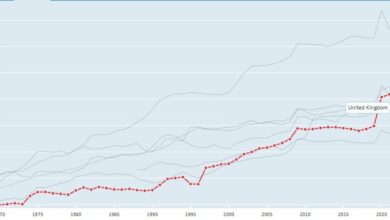

The consequences of

the brief monetarist experiment for the real economy are well known.

Lankester recounts that his wife’s family-run textile firm was

forced into liquidation in late 1980. The combination of high

interest rates, and the impact of these together with North Sea Oil

on the exchange rate, crippled the traded goods sector. Unemployment

rose rapidly and didn’t come down when inflation eventually fell.

He argues, correctly in my view, that a more gradualist policy of

reducing inflation would have been far more preferable, because it

would have avoided such a large and long lasting increase in

unemployment, albeit with a more gradual reduction in inflation. In

addition my own view is that deflation early on using fiscal rather than monetary policy

would have avoided such a big hit to the traded sector.

One mistake some

opponents of Thatcherism often make is that high unemployment was all

part of the plan, and in particular a means to reduce union power. In

fact few of those advocating monetarism before it happened believed

it would have such devastating effects. Lankester writes that

“Thatcher was undoubtedly surprised and upset by the rise in

unemployment in the early 1980s”. Interestingly he also thinks that

if she had been told about those costs in advance, she would have

gone ahead with the policy anyway because she wouldn’t have

believed the predictions, because she had this primitivist belief in

monetarism and because she would not have been content with a more

gradual fall in inflation. She really did believe there was no

alternative.

Thatcher’s

monetarist experiment was a macroeconomic policy blunder of the

highest order, because it ruined so many people’s lives and because

there was a better alternative. For those looking for a detailed and

objective account of this blunder, then this is an excellent book. It

was probably not the first time a Prime Minister or Chancellor had

pursued an economic policy that was opposed by most academic experts

and which had ruinous macroeconomic consequences, and unfortunately

it would not be the last. Over the last fourteen years we have had

two more (austerity and Brexit).

Yet the recent

example that reminds me most of Thatcher’s monetarism is Truss’s

fiscal event, which involved a Prime Minister’s primitivist belief

(for Truss that tax cuts had to be good and might pay for

themselves), a small band of economists with unconventional and

radical ideas not backed by evidence, a disdain for conventional

academic views or civil service advisors and a policy that

dramatically increased interest rates. Fortunately for us that fiscal

event was quickly reversed and its champion deposed, so it did not

create the lasting scars that Thatcher’s monetarism did.

[1] To give one

example, my first job in HMT included writing briefs for the

Chancellor, Dennis Healey, on other major economies for the

international meetings he attended. Healey wanted to know about macro

policy in each country, as well as how it was working. With a change

in government, where Howe replaced Healey as Chancellor, those briefs

now contained personal details about each finance minister, their

interests and hobbies etc, and included much less macroeconomics.

[2] To take just one

example, the incoming Conservative government chose M3 as their money

supply target in part because there seemed to be a close correlation

between it and prices two years later. HMT agreed to publish a paper

looking at this relationship, written not by HMT but by a named

Treasury economist, which turned out to be me under the supervision

of Chief Economist Terry Burns. The relationship fell

apart the moment it was econometrically interrogated.

[3] For primitivist

monetarists, facts and research have little impact on their beliefs.

When the Treasury published my research on money to price regressions

(see footnote [2]), although there was no attempt to censor what I

wrote as the named author of a Treasury Working Paper, I had to focus

on the results rather than my interpretation of them. Any objective

reading would have quickly understood that my work undermined

government policy. Yet a day after publication Tim Congdon, a well

known monetarist, wrote a piece in the Times that suggested the

opposite.

I was furious at

this, and asked to write a letter in response correcting his

misinterpretation. HMT said no. But Henry Neuberger, who as I noted

earlier was now working for Michael Foot, came to my rescue and wrote

a very similar letter to the one I wanted to write. To his credit,

Terry Burns also arranged a lunch between him, Congdon and me, where

I not only told Congdon why he was wrong but where Terry backed me

up. The results were eventually published in an academic journal

here.

[4] My own personal

story as a Treasury economist in charge of looking at the economic

effects of the budget is described

here. The story illustrates that most Treasury

economists, like the famous 364 academics who wrote the famous

letter, thought it was a bad budget.

Source link