In my last post

about the prospect of Labour breaking its tax pledge, I did something

I don’t often do, which is indulge in some ‘I told you so’s.

In doing this I was reminded that there was one other major criticism I

had of Labour’s initial economic strategy besides their

underestimation of how much taxes they would need to raise, and that

was their position on Brexit. Labour’s basic position on Brexit is

that it has ruled out not only rejoining the EU, but also joining its

single market, or even its customs union.

It should be said

that there are important discussions going on that will ease the

cost of Brexit in specific ways that are important to particular

areas of the economy. But these initiatives, even if the EU plays

ball, will not amount to very much in terms of the aggregate economy.

It remains the case that if Labour want to undo the economic damage

caused by Brexit in a significant way, they need to either rejoin the

EU’s customs union or its single market (or both).

Labour’s rhetoric

towards the EU is also a lot more friendly than their predecessors.

Rhetoric is important, particularly in countering the populism of the

right. It remains the case that one of the most potent attack lines

Labour and other political parties have against both Reform and the

Conservatives is that these are the parties that brought us Brexit.

It is potent because

most voters, including many Conservative and Reform supporters, think

Brexit has failed the economy. A recent

YouGov poll showed that only 11% of voters thought

that Brexit had so far been more of a success, while 62% thought it

had been more of a failure. Even among either Conservative or Reform

voters, more thought it had so far been a failure than thought

it had been a success. According to the

same poll, the main reason for this verdict is an

accurate belief that Brexit has damaged the economy.

Yet even in terms of

rhetoric, Labour’s position is still not as strong as it could be.

This is because Labour continue to talk in a vague way about the

Brexit deal that the Conservatives did, rather than the basics of

Brexit itself. Rachel Reeves recently talked about a “rushed and

ill-conceived Brexit”. That is fine in attacking the Conservatives,

but it allows Farage a simple get out clause, which is that it wasn’t

his deal but Boris Johnson’s. Labour cannot respond by saying

Farage also wanted to leave the EU’s customs union and single

market and that is what has caused most of the economic damage,

because Labour also appear committed to exactly that type of Brexit deal.

In policy terms, it

is very hypocritical of Labour to say that it focused on growth, and

at the same time ignore two policy changes that would have a really substantial positive effect to promote growth. Of course both Starmer

and Reeves know this. The eventual 4% reduction in GDP assumed by the

OBR is well known, but over two years ago I

noted that work

by John Springford implied that 4% was an underestimate.

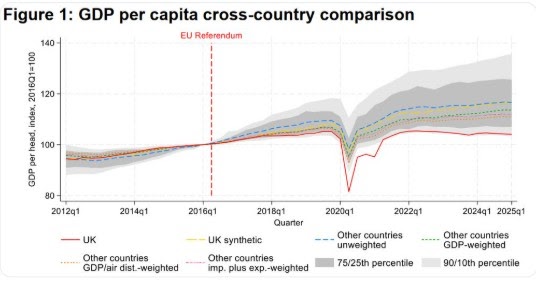

A new

NBER working paper suggests the same, saying that

productivity may already be 4% lower than it would have been without

Brexit, and GDP 6-8% lower. This chart helps show why that might be

the case (HT@davidheniguk.bsky.social).

The reason Labour

have ruled out rejoining the EU’s customs union and single market

is not because they discount the economic benefits of doing so, but

because they (and/or their political advisers) believe that to do

either would be politically dangerous for Labour.

There are two

reasons why it might be politically dangerous, and it is important to

distinguish between the two. The first is that voters would not

appreciate the government spending time and energy embarking on a

major negotiation with the EU, and the internal debate that this

would provoke, so soon after the years in which tBrexit appeared to

paralyse UK politics. The second is that rejoining the EU’s customs

union and single market, although perhaps popular with most voters,

would still upset some of its own (2024) voters in key Labour

constituencies (e.g. the red wall).

If the first reason

was the most important, then Labour could be honest with voters and

simply say that now is not the time. By saying sometime but not now,

Labour could also be honest about the damage being outside the EU’s

customs union and single market is doing. Many may not agree that the

time is not right to make such a major step back towards being part

of the EU, but at least the conversation would be about when, not if,

and the costs of delay could be discussed more explicitly.

However I suspect

the second reason is more important for Labour. This is just one

part, albeit a very important part, of their conviction that they

must on all accounts not upset socially conservative Labour voters.

It goes hand in hand with adopting much of the right’s rhetoric, as

well as adopting pointlessly cruel or harmful policies, on

immigration. This, at least as much as the tax pledge, is this

government’s

original sin.

Should Labour see

Brexit as part of their attitude to socially conservative voters, or

is there something in addition which is special about Brexit? A good

way to answer this question is to listen to Anand

Menon’s recent masterly talk

on the subject. But a key point must be that there has been a rise in

right wing populism around the world, including

Europe.

This strongly suggests that Brexit was essentially a manifestation of

this growing popularity, rather than a cause of it. Whether you view

this rise as due

to the economic consequences of neoliberalism

or not, Brexit can be seen as just one of the many manifestations of

the growing popularity of right wing populism.

As I and almost

everyone else has said repeatedly over the last several months,

Labour’s strategy (the McSweeney/Blue Labour strategy)

of adopting populist right positions on socially

conservative issues might have been sensible in opposition but it

does not work for Labour in government. When in opposition, most

social liberals would still vote Labour where it mattered because the

primary goal was to defeat the Conservative government, and in most

constituencies Labour were best placed to do that. Now that they are

in government, Labour taking socially conservative positions worries

social liberals much more, which is one reason why Welsh nationalists

replaced Labour in a recent by-election and why the Greens are

advancing in the polls.

.

While this is the

general reason why Labour’s current stance on Brexit is untenable,

there are two specifics that relate to their Brexit pledge. The first

is the size of the boost to growth that either joining the EU’s customs union or single market would give. This is likely to be bigger than anything else this

government could do to increase living standards. Once again, the

fact that Labour are now in government rather than opposition is

critical. To see the importance of incumbency on voter decisions,

look at the swing from Trump in 2024 to the Democrats in recent

elections, a

swing that is all about the economy. A little of that

swing may be due to Trump’s tariffs, but fundamentally it is that the cost of

living remains a problem, and voters blame whoever is in government

for that.

The second specific

reason Labour’s Brexit position is untenable is that, like the tax

pledge, it was very likely to constrain Labour not just after the

2024 election, but in future elections as well. Using the last Labour

government as an example, Labour were always likely to find it harder

to get elected the longer they were in government. If this is the

case, both the Brexit pledge and the tax pledge would in effect bind

Labour until they got voted out of government, because the electoral

arguments for making these commitments would only increase over time.

For both tax and

Brexit this is an impossible position for Labour to put themselves

into. With tax, because health costs trend up over time (as they have

done in almost every country over the last few decades) and with a

commitment to increase defense spending as a share of GDP, major

taxes just have to rise at some point over the next decade [1], even

if you ignore the arguments for increased public spending now.

Equally with Brexit

simple

demographics mean that the number of voters who are

opposed to Brexit will only increase over time. As a result, Labour’s

pledge not to fundamentally alter the terms of Brexit is not tenable

over the next decade. Labour, and to be honest much of the country,

are in desperate need of stronger economic growth right now, and so

it would make sense [2] for Labour to follow the abandonment of their tax

pledge with initiating discussions on how Great Britain could rejoin

the EU’s customs union. [3]

[1] The best way of trying to reduce this upward trend is to spend more on preventative health, as the IPPR argues here. However that takes a lot of investment and is unlikely to yield quick benefits.

[2] Of course it making sense does not mean that it is what Labour will do. It is Labour’s fiscal rule that is forcing it to (probably) break its tax pledge. With Brexit there is nothing similar to overcome a misguided strategy and force Labour’s hand.

[3] As I

argued here, it makes sense in political terms to

rejoin the EU’s customs union before its single market.

Source link