The UK macroeconomy

was one of the big stories of the previous two weeks, so you might think this blog

post should have covered it earlier. However my guess at the time was that

media coverage was a bit like a nervous flyer who, when the plane

hits a bit of normal turbulence, decides it’s is going to crash

and everyone will die. As I’m not a journalist, it seemed better to

wait a week to see if I was right.

I’m glad I did.

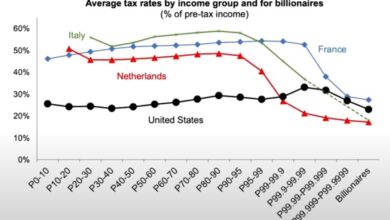

This is what got the media so excited about, and what happened next

From around the 6th

January interest rates on UK 10 year government debt rose over a week from around

4.6% to around 4.9%. But then interest rates fell back as quickly as they had increased to around 4.65%.

Was this a UK or

global blip? To answer that we need to look at US rates.

We see something

very similar, but of slightly smaller amplitude. This tells us that

what we saw in the first half of January was mainly a movement in

global long term interest rates, with a little bit of UK specific

icing on top that largely disappeared once the latest UK inflation

data came out.

I’ll come to why

this might have happened in a minute. But why did virtually the entire the UK media get this all so wrong? The main lesson here is

that data is volatile, and you can have a lot of egg on your face if

you treat every short term movement up or down as permanent, or worse still the beginning of a

trend. It’s a lesson that all economists know but journalists are

increasingly paid to forget. But that is not the only reason

journalists got over excited a week or two ago.

Another is the Truss

fiscal event. Conservative politicians, and those journalists aligned

to them, are desperate for Labour to suffer something comparable to

what happened to the Conservatives under the leadership of Liz Truss.

So they are tempted to shout fire whenever they see a puff of smoke,

even when that smoke looks like it’s mainly coming from a long way away! That then led other journalists to feel they had to cover the

same story, and political journalists put a UK political spin on it

because that is what they do.

When journalists

cover anything to do with fiscal policy, we know from long experience

that the language and reasoning they use can be very different from

the macroeconomics taught in universities. I call it mediamacro. It

involves for example treating the government as if it’s a household, treating

deficits

as a sign of political irresponsibility, and personifying

financial markets as a kind of vengeful god. As is often the

case, it is much better to read good academic economists, like

Jonathan Portes here, than the stuff most journalists

write.

The end result of

the media’s uninformed overreaction and distorted coverage was that many people were seriously misled, and

the media almost manufactured a crisis out of nothing. In case you

have forgotten, just a week ago newspapers

were speculating that Reeves was about to be sacked

and who might replace her, all because of largely global movements in

interest rates over which she had no influence. I used the word

melodrama in the title of this post, but I could have equally used

madness.

What caused the

upward blip in global longer term interest rates? To be honest, who knows and who

cares? When I was much younger I was approached about

moving to a much better paid job working in the City, and I said no

because I thought worrying about such things would soon bore me to

tears. I found real macroeconomics much more interesting, and still do.

If, unlike me, you are interested in short term bond market fluctuations, here

is the Toby Nangle looking at what evidence we do

have, and here

is Paul Krugman speculating that it might be all about

Trump. It must certainly be true that as a result of Trump becoming

POTUS, the degree of macro policy uncertainty has shifted sharply upwards and

this will mean longer term interest rate movements are likely to

become more erratic.

What about the

exchange rate? Sterling did depreciate in January, and that hasn’t

been reversed, but the

scale of movement is small and therefore not at all

unusual, so once again there is nothing of interest here unless you

speculate on currency movements.

This whole episode

did raise two other issues that are worth discussing.

Fiscal

vulnerability

Because Reeves like

previous Chancellors has pledged to follow the golden rule, which is that day

to day (current) spending should over the medium term be paid for out of taxes. As a result, anything that looks like it will increase spending over the medium

term will lead to speculation of what other items of spending will be

cut to compensate, or whether taxes will have to rise. Higher long

term interest rates mean higher spending servicing the government’s

debt.

The most important

point here is to again ignore a lot of what you read or hear in the

media. First, the fiscal rule that Reeves is committed to looks at

the expected balance between spending and taxes in a few years time, so there

is absolutely no need to cut spending in the short term. Second, there are

all kinds of macroeconomic developments that could have an impact on

the government’s current deficit in a few years time, so this kind

of thing will happen constantly. As a result, and as this episode

clearly illustrates, it is generally better to wait and see rather

than react immediately. Third, there is no reason why higher spending

in one area has to be met with lower spending elsewhere. It can also

be met with higher taxes. That the media tended to talk about

spending cuts rather than higher taxes has no macroeconomic

justification.

So Reeves was

absolutely right to ignore all the media hysteria. However it has to

be said that Reeves did earlier make two mistakes that contributed to

the way the media covered this aspect of the story. First, the fiscal rule that balances current

spending with taxes used to apply to forecasts five years ahead, for

good reasons. In the Budget she changed this so it will eventually

apply to just three years ahead, which was

simply a bad decision. Second after the budget Reeves

made the mistake of appearing to rule out significant increases in

taxes in the future.

Many react to talk

about spending cuts by blaming this particular fiscal rule, but that in my view

is a mistake. As long as the golden rule looks far enough ahead, any

short term volatility caused by fluctuations in spending or taxes is likely to be reflected in volatile economic reporting rather than erratic economic policy, and it is a mistake to conflate the two. I

put the case for the golden rule as a fiscal rule

here.

Short term

economic growth

The second lesson is

about data on economic growth, which was also mentioned frequently in

reporting. However monthly or quarterly growth figures are also

erratic, so the lesson about not being misled by short term

fluctuations in the bond market also applies to growth figures. The

Conservatives are currently boasting that they left office with

economic growth the highest in the G7, but because that is based on a

particular quarterly growth rate it is a meaningless claim.

Equally any impact

policy may have in increasing underlying growth normally involves

considerable lags. It is very unlikely that anything the new Labour

government has done will have had any impact on the growth numbers

currently being reported (i.e. end 2024). If policy has anything to

do with recent growth numbers, it is the policy of the last government.

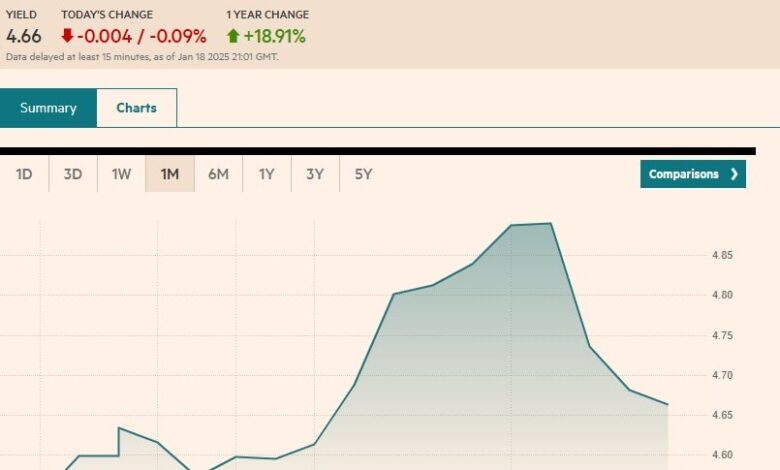

To take just one

example, you will read a lot about how employers dislike the NIC hike

imposed in the budget. Below is the OBR’s assessment of the impact

of this on GDP, alongside the impact of the modest increase in

public investment also announced then.

They estimate that

higher employers’ NICs will reduce the level of GDP by 0.1% in

financial year 2026/7. Less than half of that will occur in the

forthcoming financial year. These estimates are relatively uncertain,

but anything much larger or quicker is pretty unlikely. While it is easy for a journalist to link the October budget to recent growth data, that does not mean that in reality there is any causal link at all.

What this chart also

shows is that fiscal policy can boost demand and therefore growth in

the short run, as long as this impact is not offset by a more

restrictive monetary policy. We are on more solid ground in quantifying these effects.

The last budget was expansionary, and should boost GDP growth in

2025/6 by around 0.5%. To the extent that Labour are ‘kick-starting

growth’ this is it, but don’t expect to start seeing it in the

data until at least six months time.

Although monthly or

even quarterly changes in economic growth are not very interesting,

growth in the longer term and the impact the Labour government might have on it are worth discussing. These questions, rather than mediamacro melodrama, are subjects I hope to return to fairly soon.

Source link