This, my final post

on the forthcoming budget, is designed to provide a guide to how to

read what Reeves announces (or doesn’t announce) in a way that goes

rather deeper than the normal media commentary. My perspective, along

with a large part of the UK population, is how much does the budget

get us on a path designed to end public service austerity. (See

here for what I mean by that.) As I argued here, a budget that focuses on filling black holes rather than restoring public services will be a political failure. So I will start with

current public spending, go on to talk about what taxes might be

raised to match that spending, and finally talk about public

investment.

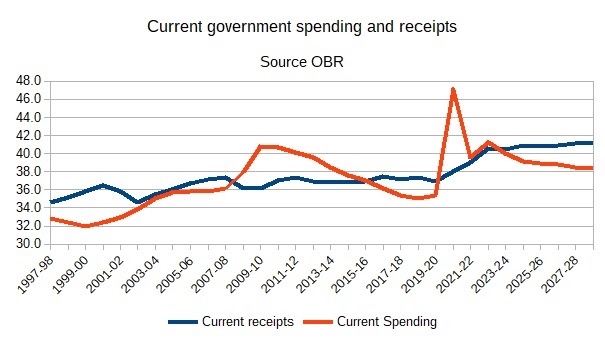

Public spending

As I outlined in

an earlier post, the share of public spending in GDP

needs to rise substantially to get back to an acceptable level of

provision. Below are the headline numbers for total current spending

(excluding gross investment) and taxes from the OBR’s

databank. We see the share of public spending in GDP

rise under the last Labour government and fall under the

Conservatives. The pandemic (with a little earlier help from the

Johnson government) provided a sharp increase, but the plans Reeves

inherited suggest a resumed decline.

A critical point

that I made in that earlier post, which is routinely ignored in most

analyses, is that this GDP share needs to rise over time because, in

the UK and most other countries, the share of health spending in GDP

has historically been on an upward trend for well known reasons. In

that post I estimated that, compared to levels today, current public

spending needed to rise by 3% of GDP to return to 2010 levels of

public service. However a better point of focus is the end point of

the OBR’s projections, and because of the decline in spending

Reeves has inherited the increase in spending has to be over 4% of

GDP by that date.

Although a spending

review for that period is yet to take place, Reeves will have to give

the OBR some indicative numbers, and these are what we need to focus

on. I don’t expect to see the share of current spending rise from

its 2023/4 level of 40% to 43% by the end of this decade, if only

because restoring public services to 2010 levels is a ten rather than

five year project. The key question is how far will Reeves go, which

in turn will depend in part on how much she can raise in tax, and in

part on the forecast the OBR gives her. As I

noted in my first post on the budget, economic growth

does not give you much in the way of additional resources for public

spending as a share of GDP, unless it is accompanied by public sector

productivity gains.

The OBR publishes

revised numbers for current public spending immediately after the

budget. There is always a risk that there will be an element of

Treasury/Cabinet game playing in the numbers Reeves gives the OBR,

However I would have thought anything less than a projected real term

increase in departmental spending, after allowing for much more for

the NHS, would be politically disastrous for the government. In

addition it will be very difficult (and wrong!) for Reeves not to at

least begin rolling back child poverty, and in particular abolishing

the two child limit and benefits cap. (See

this from the IFS on the impact of these policy

options on poverty.)

Tax increases

For tax increases

the numbers you will see in budget commentary will be in £ billion

(or £ million), so to give you an idea of scale raising public

spending by 1% of GDP in today’s prices will cost around £30

billion by the end of the decade, and after adding in inflation more

than £33 billion.

The tax rises in

Labour’s manifesto are small in comparison. VAT on private school

fees, a higher windfall tax on energy, closing non-dom loopholes and

ending the carried interest tax exemption raise about £4 billion.

Labour also hopes to raise £6 billion by spending more on tax

collection, but the OBR will need to make a judgement about how

realistic that is.

There are some tax

increases due to come in that were scheduled by the last government,

most notably the freezing rather than indexing of tax allowances. In

addition Covid business tax relief is due to end, fuel duty is due to

rise (ending a temporary cut and adding in uprating which the last

government routinely assumed but never did), and lowering the stamp

duty threshold. Reeves could reverse any of these, but that would

only add to the taxes she needs to find elsewhere.

So where are large

tax increases going to come from? Reeves has pledged that they should

not come from ‘working people’, but in practice that seems to

mean not from income tax, personal NIC contributions and VAT. Labour

has also pledged not to raise the rate of corporation tax. What is

left that would yield large amounts of money?

-

Employers

National Insurance Contributions

Raising the

contribution rate by 1% for employers would

raise about £5 billion net. (Beware larger

numbers quoted in the media that include contributions paid by the public

sector.) Another possibility is to extend national insurance payments

to employers’ pension contributions, which could

raise £12 billion (net of the public sector). Finally

she could remove the NIC higher earnings cap, which could raise over

£12 billion. Strangely (not really!) this possibility is hardly ever

discussed in the media. It is one of the steps needed to make

national insurance contributions more like income tax, with perhaps

the

eventual integration of the two taxes on income from

employment, but Reeves may feel it is precluded by Labour’s

pre-election promises.

-

Capital Gains

Tax (CGT)

At present, capital

gains are taxed at a much lower rate than incomes, which if nothing

else leads to a lot of tax avoidance. The details of what Reeves

could do quickly get quite complex, as are estimates of how much the

tax increase would raise. The key uncertainty is how much owners will

(initially at least) hold on to assets to avoid paying the higher

tax, hoping for a change of government. The OBR will have to take a

view on this. Equalisation is also not straightforward, because it

could involve just income tax, or it could involve all taxes on income from employment

including National Insurance. A

recent study suggested that equalisation with income

tax (with rates of 20%, 40% and 45%) plus a system of allowances and

other changes could raise £14 billion. Leaks

to the Guardian suggest Reeves is looking at increases

in the CGT rate from 20% (for most) to between 33% to 39%.

-

Investment

income

Reeves could raise

the tax rate on rental and dividend income. These are currently taxed

at similar rates to earned income, but they could be taxed at higher

rates. More radically, she could extend National Insurance

Contributions to investment income, which Advani estimates could

raise £11 billion.

-

Inheritance

tax

Raising this from

40% to 45% would only raise a billion according to the IFS ready

reckoner. (I would advocate a much bigger rise – sorry kids! – on

equity grounds.) There is probably more scope to raise money by

removing

various exemptions (e.g. business and agricultural

reliefs are worth 2 billion), and Reeves could be more radical still

and replace it with a gifts tax. I don’t expect it, but Reeves

could also introduce a wealth tax. Advani suggests a 1% annual tax

would raise £13 billion.

-

Extending the

freeze on tax thresholds

These are currently

frozen until April 2028. Reeves could extend these over the full OBR

forecast period, raising around £8 billion, but this really is an

income tax increase. Budget leaks suggest she intends to do this, and

perhaps she thinks this is politically safe as the Conservatives will

find it difficult to condemn her for continuing what they started.

There are a lot of

detailed changes that Reeves could make, which tend to be small in

revenue terms but can add up. For those who want to get into the

nitty gritty of all that and the above, there are plenty of good

resources around from, among others, the IFS (their ready

reckoner and Green

Budget), the Resolution

Foundation, Centax, the

Financial Times and Dan

Neidle.

The numbers above

indicate that there is clear scope for substantial increases in

taxes, even within the limits Labour has imposed on itself (with help

from the Conservatives). Whether they amount to enough to bring

public services back to 2010 levels is more doubtful. Most, but not all, of the

proposals mentioned above will mainly hit individuals who are well

off. Unfortunately the obvious redistributive tax change, raising taxes on very high earned income, is probably ruled out by Labour’s pre-election pledges.

Two final points.

The first is to look out for tax increases that could be extended

further in later years. In many cases gradualism makes economic

and/or political sense, and also see the point about Cabinet game

playing above. The second is to see if Reeves makes any initial moves

to introduce new taxes, such as road pricing for example.

Public

investment

There

has been plenty of discussion in the media of how she could amend the

‘falling debt to GDP’ fiscal rule to allow more borrowing for

investment, and almost no discussion of my own preferred option of

getting rid of the rule completely. This makes perfect sense as the

rule is designed to appease mediamacro rather than economists or the

markets!

Whatever

she decides to do, the key issue is how much extra public investment

she plans for by the end of the OBR’s forecast period. On present

plans net public investment is set to fall from 2.5% of GDP currently

to 1.7% by 2028/9. In my view this decline needs to be turned into a

substantial rise if we are going to catch up with all the investment

lost under the Conservatives.

As

the budget is on Wednesday next week, I will not do the usual post of

Tuesday, but instead delay it until Thursday or Friday to give my

own reactions to the budget.

Source link