In her October

budget the Chancellor raised total government spending by 1.8% of GDP

compared to the plans of her predecessors, which means that total

public spending as a ratio to GDP stays pretty flat over the 5 year

forecast period. (Anyone who calls this the share of government

spending in GDP is either being sloppy or deliberately misleading.

[1]) As a result, that ratio is planned in 2029/30 to be roughly

where it was in 2022/3, the penultimate financial year of the

Conservative government.

Just before the

budget, I calculated that spending to GDP needed to be about 3%

higher than this to ‘end austerity’, by which I meant return public service provision to a level similar to the final

years of the last Labour government. However the method I used to get

to that figure was based on some unfamiliar data sources, so I thought it

might be useful to redo that calculation using more familiar

definitions. This post does that.

What you cannot do,

but which so many do, is look at the total ratio of government

spending to GDP and draw conclusions from that alone. Invariably such

exercises equate a constant level of this ratio over time with a

constant provision of public services, but this is completely wrong.

For example, total government spending includes the interest the

government pays on its debt, but it would be silly to suggest that

the public services have improved since the pandemic because interest

rates on that debt have significantly increased. The ratio of total

public spending to GDP was unchanged between 2007/8 and 2016/17, and

as a result I still get some people telling me that therefore

austerity over this period was a myth. Clearly we need to look at

some level of disaggregation.

Before I do so, it

is worth noting that it isn’t easy to get hold of historical time

series that break down the public spending total into its components,

including how much each department has received over time. The ONS do

publish a quite detailed breakdown by spending

function, but for individual years rather than as a time series.

Thankfully the IFS has done much of the legwork here,

and I’ll draw on this source extensively. Those who want to avoid

my analysis and jump to my conclusions can skip to the text after the

final table.

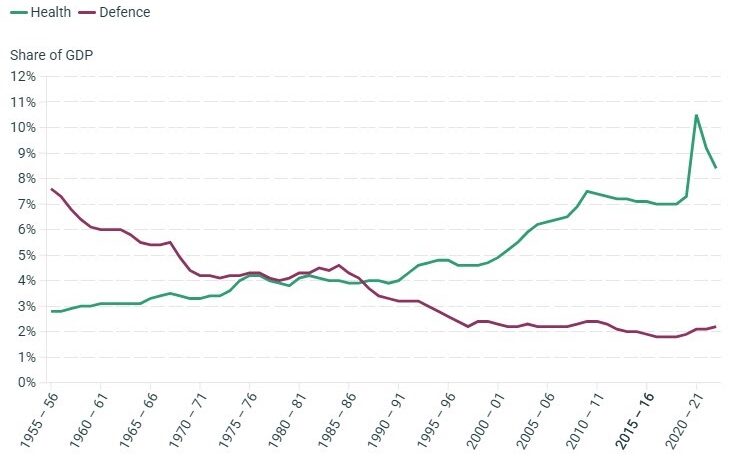

Even if we

disaggregate total spending into its major components, it is still

true that keeping some part of public spending as a proportion of GDP

constant over time is not necessarily keeping the level of public

provision constant. This point can perhaps be made most clearly by

noting that as GDP grows the share of food purchases in total GDP

tends to fall, but it would be daft to report this as implying that

as economies grow people are getting hungrier. The two items of UK

public spending that have shown the clearest trends in the past are

health and defence. Here, from the IFS document referenced above, are

those shares over time.

Defence spending is

now almost a quarter of what it was in 1955, reflecting both the

abandonment of the UK’s imperial role and the end of the cold war.

Obviously this does not mean people feel less secure than they used

to. Health spending as a share of GDP has been steadily going up over

time for a number of reasons. To the extent that this is because the

population is getting older and therefore needs more care, it does

not imply that we are on average healthier but just that life

expectancy has increased. A clear example of this point is that

during the decade after 2010 the share of health spending in GDP only

fell slightly, but waiting times for treatment increased much more

dramatically, correctly suggesting the level of public provision of

health services had deteriorated substantially.

The chart below

compares the public spending ratio with and without health and

defence spending, and they look quite similar. However this is

largely a coincidence, and critically the future looks very

different, because probably both ratios will need to rise in the

future. As a result, since the start of the century when defence

spending stopped falling, and for the foreseeable future, we should

expect to see the total public spending ratio (and therefore for the

share of total taxes in GDP) to rise over time. I apologise for going

on about this, but this basic point is hardly ever made in mediamacro

commentary.

Total UK public spending as a ratio of GDP including and excluding health and defence

Of course health and

defence are not the only areas of public spending where spending as a

share of GDP may rise or fall over time even though public provision

remains the same. Another example would be the implications of baby

booms for education spending. However the upward trend in health

spending is so substantial that some analysis is required. We cannot

just fit a trend line through the data, because for much of this

period health provision has been too low. Health spending is unlikely

to be too high very often because raising taxes to finance it is

painful, but Conservative governments since 1979 have squeezed

spending. For this blog post I’ve tried to get a handle on this by

looking at total (public and private) health spending in other

countries using OECD data.

In almost every OECD

country where data is available from the early 1970s there is a

pronounced upward trend in the GDP share. The trend varies across

countries as we would expect, but an average across 19 OECD countries

implies that health spending to GDP rose by 0.11% each year, with

roughly an equal number of countries above and below this figure.

(The UK number is 0.145%.) As the pressures leading to this ratio

rising are common across most countries, it seems reasonable to use

this 0.11% figure as a measure of the underlying trend in the health

to GDP share..

All that remains to

decide is when UK health spending was sufficient. I have chosen 2010,

because waiting times for treatment at this point were tolerably low.

This allows us to measure the spending gap in other years, and also

to project this trend forward in assessing the adequacy of future

plans. Of course this approach is very rough and ready. It may also

be possible to reduce this trend in the future by increasing the

amount of preventative care (see the discussion here),

but that is not going to happen when health is underfunded because

treatment will always get prioritised.

Finally I have used

data from the IFS to compare GDP shares and ratios across categories

of spending between 2007/8 and 2022/3. [2] The earlier year is a

useful reference point because it is before the recession that

followed the financial crisis (recessions tend to raise spending in

some areas) and is not affected by subsequent austerity. As I have

already noted, the current planned total spending ratio for 2029/30

is similar to 2022/3.

Components of public spending as a

share of GDP

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The chart above

suggests health spending in 2022/3 was around 0.5% of GDP below what

it needs to be to replicate 2007/8 levels of provision. Actual

provision was undoubtedly worse in 2022/3 because of the hangover

from the pandemic. Hopefully that will have dissipated by 2029/30,

but equally the underlying upward trend in health spending will mean

that spending will need to rise by just over 0.5% between 2022/3 and

2029/30. On this account the total public spending total needs to be

1% higher in 2029/30 to replicate 2007/8 levels of spending on health

grounds alone.

Turning to

education, allowing for changing student numbers still suggests that

public provision in 2022/3 was significantly below 2007/8 levels.

This assessment seems to roughly correspond with media reports of

inadequate provision (see here

for example). Turning to other social security, levels

of deep poverty in 2022/3 were similar to 2007/8, but

spending has fallen, suggesting another significant fall in public

provision here. (The two child limit needs

to end, for example.) Current problems in the

provision of public order and long term care have been well

documented. (Here is a very recent IFS report on justice.) If we allow for a public spending gap worth around 0.5%

of GDP in each of these four sectors, then adding in health implies

we need the total public spending ratio to be 3% higher in 2029/30

than current plans to replicate the level of public spending

provision seen in the final years of the last Labour government. [4]

A 3% gap just

happens to be the same number I calculated before the Budget using a

rather different approach. Any increase in the defence spending share

needs to be added to that. This analysis

confirms that Labour’s spending plans remain substantially

inadequate if the aim is to return public provision to levels seen in

the final years of the last Labour government.

Of course current

plans only go five years ahead, and Labour may be in power for longer

than that. It was only in the second term of the previous Labour

government that public spending increased substantially. There are

various reasons why the political situation is similar and different

to then. My more substantive concern is that the Chancellor shows no

sign of having done the kind of analysis shown above, but I am happy

to be corrected (in confidence) if I am wrong about this. [5]

My analysis suggests

that repeating Labour’s commitments on the main areas of tax going

into the next election would be very foolish, but I fear the

political pressures to do so will be great, and that this government

will succumb to those pressures. There is a nasty feedback loop here.

The more public service provision fails to noticeably improve over

the next few years the more Labour will feel it needs to make

unrealistic pledges on tax to win the next election. One way of

avoiding that was to have increased taxes by more in the last Budget.

.

[1] Calling this

ratio a share implies that the rest of GDP is the non-government

share, but it’s not because total government spending includes

transfer payments.

[2] Data for

overseas aid is for 2021/2 rather than 2022/3.

[3] There are many

areas of public spending not included in this list. For example

summing each column gives 32.4% for 2007/8 compared to 40.3% for

total public spending. The total public spending ratio in 2022/3 was

44.8%. Compared to 2007/8 debt interest explains about half this

increase, but I would really like to know what explains the rest.

[4] The level of

debt interest in 2029/30 is expected to be only a little below 2022/3

levels, reflecting an assumption that interest rates will not fall

back to levels seen in the 2010s. If this does turn out to be the

case, higher debt interest should imply higher taxation rather than

lower public spending. There is no reason why higher interest rates

should shift voters preferences between publicly and privately

provided goods, so saying that other public spending should fall to

match higher debt interest is as absurd as saying spending on food

should fall by this amount. Higher taxes allows the cost of

additional debt interest to be spread across all areas of consumer

spending.

[5] Attitudes within

the Treasury, and in particular a belief that it is up to departments

to make the case for higher spending, do not help here. Such an

approach often precludes a common overall framework and leads to

outcomes that can have more to do with the character of individual

politicians than social needs and preferences.

Source link