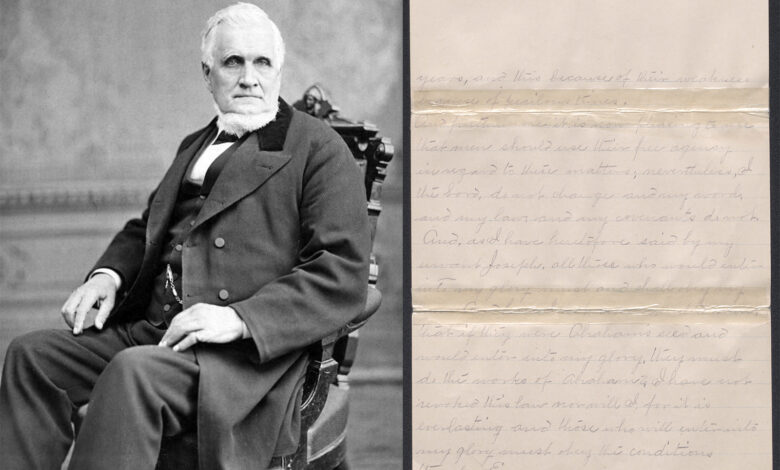

(RNS) — In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a religion built on modern revelation, perhaps no revelation has caused as much controversy as one attributed to President John Taylor, who presided over the church in the 1880s during one of its most tumultuous decades.

In 1886, while the federal government sought to stop all Mormons who practiced polygamy, Taylor allegedly wrote a revelation proclaiming the controversial practice was an everlasting covenant that could never be revoked. Such a command quickly became complicated when the church renounced the practice in 1890. LDS authorities then publicly and vociferously denied his document’s existence for over a century.

That is until Saturday morning (June 14), when the revelation quietly appeared in the church history library’s catalog.

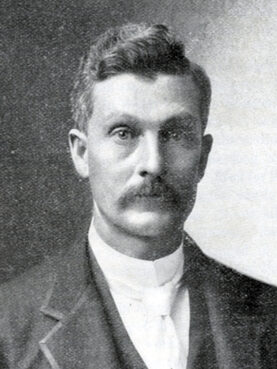

What happened to it in the intervening 130-plus years? The revelation was for years in the hands of Taylor’s son, John W. Taylor — a slim, stern man with well-manicured hair, a conservative mustache and a piercing gaze. John W. Taylor was groomed for Mormon leadership and ordained an apostle himself at 26 years old in 1884, four years after his father became the faith’s prophet.

John W. Taylor, son of John Taylor. (Photo courtesy Wikimedia/Creative Commons)

The elder Taylor spent much of his presidency hiding as government officials prosecuted and imprisoned those who practiced plural marriage. He died in 1887, separated from family and out of public sight. John W. Taylor always maintained his father had exhibited profound bravery in his refusal to acquiesce.

While the next LDS president, Wilford Woodruff, publicly forfeited polygamy in 1890 to ensure the church’s survival, John W. Taylor rejected any such concession: Polygamy was an eternal law, he believed.

He and a handful of other authorities secretly continued to solemnize plural unions, and the young apostle was sealed to three additional wives. This prompted the church in 1904 to issue the “Second Manifesto,” telling members they must cease all plural marriages for good.

John W. Taylor refused and lost his place in the Quorum of the Twelve, forfeiting his ecclesiastical office instead of betraying his father’s principles.

But being dropped as an apostle wasn’t the end of his church discipline. After being caught solemnizing more polygamous unions, he was summoned to an excommunication trial. At the hearing, he displayed what he alleged was the 1886 revelation from his late father, written in President Taylor’s own hand, proclaiming polygamy could never be revoked. John W. Taylor was excommunicated. And when he died in 1916, the document crucial to his defense remained within his family.

Over the ensuing two decades, an increasing number of Latter-day Saints became convinced the church had erred in renouncing polygamy. They congregated around men who claimed to have been appointed by President Taylor himself in September 1886 to a priesthood council authorized to continue the principle even if the church strayed. At the heart of their narrative was the revelation that John W. Taylor had displayed at his excommunication trial.

Finally, on June 17, 1933, after years of disputes, the church’s First Presidency issued a memo reaffirming the threat of excommunication to anyone who continued to practice plural marriage. The memo explicitly dismissed rumors of a “pretended revelation” from President Taylor and denied the document existed.

Nellie Taylor, the widowed plural wife of John W. Taylor, knew otherwise. She had spent the underground period of the 1880s hiding in Mexico and stood by her husband as they remained committed to the principle. Through an intermediary, she contacted the First Presidency within a month of the memo’s release and alerted them to her father-in-law’s revelation and where they could find it.

By July 15, 1933, the First Presidency held in its possession the document whose existence it vehemently denied. And it wasn’t a complete surprise — the church historian’s office had a copy of the text, though not access to the original, as early as 1909.

Instead of correcting the June memo’s claims, they instead sequestered the revelation. Church authorities refused to confirm its veracity.

Meanwhile, Mormons committed to polygamy soon became known as “fundamentalists,” a reference to their devotion to what they believed to be the faith’s founding principle. They continued to stake their claims on President Taylor’s alleged revelation. A photograph of the text, likely taken just before the document was turned over to LDS authorities, was frequently shared within the community, though it could never be verified.

The “Taylor Revelation,” as it is sometimes known, only grew in significance throughout the 20th century. Although many ideas found in it were featured in President Taylor’s other available documents, including several other revelations from his underground period, this text took on mythic proportions. It came to symbolize polygamy’s eternal nature and its centrality to the faith, etched in a prophet’s own hand — even if, and perhaps especially because, its existence could not be firmly corroborated.

What’s in the revelation released Saturday? Cataloged as MS 34928 and titled “John Taylor revelation, 1886 September 27,” the digitized archival file contains several documents. Besides the long-speculated revelatory text — words in faded pencil that were addressed to “My Son John” — there are several typescripts, as well as a memo signed by First Presidency counsellor J. Reuben Clark that details how the revelation came into the church’s possession.

A portion of President John Taylor’s handwritten 1886 revelation declaring that “I, the Lord, do not change and my covenants and my law do not, and as I have heretofore said by my servant Joseph, all those who would enter into my glory must and shall obey my law, and have I not commanded men that if they were Abraham’s seed and would enter into my glory, they must do the works of Abraham? I have not revoked this law, nor will I … ” (Courtesy of the Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints)

The revelation is clear in its purpose and matches the photographed text that has circulated in the fundamentalist community. “How can I revoke an everlasting covenant,” President Taylor’s God declares, when “my everlasting covenants cannot be abrogated nor done away with.” All who wish to enter into God’s highest glory “must and shall obey my law.”

While these documents do not confirm other key elements of the fundamentalist origin story — most notably, the ordination of a clandestine priesthood council — they confirm the existence of a text fundamentalists have long insisted was real.

As important as the document will likely be to fundamentalists, it raises thorny issues for Latter-day Saints. Was Taylor’s revelation true, and were the prophets who followed him traitors? And what does it mean for LDS authority if revelations — and revelators — are fallible?

The LDS church did not attempt to answer these questions. Instead, the documents appeared in the catalog without any comment or explanation. I think it is part of a process in which the First Presidency has been slowly transferring many previously restricted historical documents in its archives to the church historical department, rather than it being any kind of response to current debates about the role of polygamy in church history. But perhaps further analysis is coming.

Benjamin E. Park, historian and author of “American Zion.” (Photo by Blair Hodges)

While these documents exhibit material frailty — faded etchings, ruffled pages, jagged creases — their contents pose lasting meaning. Latter-day Saints cherish their tradition’s revelatory treasures.

(Benjamin E. Park teaches American history at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas, is the author of “American Zion: A New History of Mormonism” (2024), runs the YouTube channel Professor Benjamin Park and recently became the president of the Mormon History Association. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

Source link