Last week the IPPR’s

Commission on Health and Prosperity published its

final report. The report not only makes a number of

important recommendations for future health policy, but it also

focuses on how better health can also improve economic outcomes. I

must admit, when I was first asked to be a member of that Commission,

I did have a minor concern about this. I felt that the argument for

better health was strong enough on its own and it didn’t need an

additional economic payoff as part of its justification.

That may surprise

you coming from an economist, but it is actually a basic part of

academic economics. Academic economists typically write papers where

the aim is to increase individual and social utility, not economic

growth. As countless studies have shown, a person’s health is a key

element of their happiness, wellbeing and therefore utility. [1] But

I also understood that power in the UK lies in the Treasury, so

making the links between better health and a more productive economy

are important.

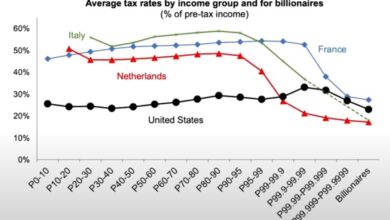

However, what I

didn’t know when the Commission was being set up was just how

crucial the interactions between health and the economy would become

for the UK in the years after Covid. Here is a chart from the report:

The pandemic led to

a rise in economic inactivity (those in the potential workforce not

working) in many countries, but that rise was partially or completely

reversed once the pandemic was over in nearly every country. The

exception is the UK, where what had been a downward trend in

inactivity became an upward trend. The report estimates that since

the pandemic just under a million workers have left the labour force

in the UK due to sickness (page 20 of the report). This is a huge

number, and impacts on the prosperity of everyone in the UK.

Why has this

happened in the UK and not elsewhere? The report debunks the idea

that it is a ‘lifestyle choice’, by showing that the increase in

inactivity is most marked among those with greater health needs or at

greater health risk. My own guess would be that this is yet another

consequence of the squeeze in resources going to health in the UK

since 2010. The NHS was just about managing even though it was

working beyond full capacity, but this meant that the UK health

system was particularly vulnerable to a big health shock, and as

waiting time data shows it has yet to show any signs of recovery from

the shock of the pandemic.

The rise in those

with long term health conditions doesn’t just lead to exits from

employment, but also lower earnings (page 17) and productivity (page

26) for those who remain. Once again, the latter in particular has

knock on effects on everyone else in the UK. For those who worry

about this it also puts upward pressure on immigration. If I had to

give two ways I was confident about how we could improve the UK’s

growth and productivity performance, it would be through additional

public investment and through improving UK health.

Most of the report

is about how to do the latter, during a period when the government is

likely to believe that money is very tight. The key emphasis is on

moving away from a health mission all about dealing with acute need

(what the report calls the ‘sickness model’, page 35), and

instead aiming to create good health (page 39). In the sickness model

personal health is seen largely as an individual responsibility, and

society only gets involved when health problems arise. The problem

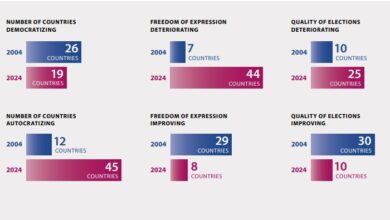

with that model is nicely summarised by this graphic from the report:

Social conditions

help determine how much people are able to take care of their health,

and with a few exceptions we have largely ignored this problem.

Focusing on the eventual effects of these social conditions rather

than the conditions themselves not only reduces social welfare, but

it is also more costly. Rising levels of obesity is an obvious

example of this.

The idea that we

should focus on prevention rather than cure is not new. What the

report does very well is systematically and broadly think about what

prevention might involve. It involves improving workplaces, for

example, by incentivising firms to reduce stress and improve the

workplace culture (page 41). It involves improving the unusually low

level of UK sick pay which will help avoid sick people coming to

work, taking longer to recover and affecting other workers. It

involves taxing unhealthy goods far more than we do at present, and

using some of that money to subsidise healthy goods (page 43). It

involves providing more help and care for our children outside school

(45). It involves reducing inequalities. And of course it involves

reorienting more NHS expenditure towards health monitoring rather

than treating illness.

For those who say

this all sounds like creating a nanny state, let me introduce you to

the basic economic idea of a Pigouvian tax. Sometimes individuals do

things that have negative effects on others, but society rather than

the individual bears the cost of those things. (We are used to

thinking about negative externalities in the context of firms and

issues like pollution, but the idea is far more general than that.) A

Pigouvain tax tries to shift the cost from society back on to the

individual. This leads to better social outcomes, and it also raises

much needed cash.

Sometimes this idea

can be applied directly, and a sugar

tax is a very good example. In other situations

applying a tax is not possible, so other incentives or regulations

need to be employed. To go into all the ideas proposed by the report

would make this post far too long, so I strongly recommend reading

the report itself (page 53 onwards). It is full of ideas, case

studies and international comparisons.

One final point.

There are so many reports around nowadays, many of which have worthy

goals but which involve additional costs to the public sector that

are often left vague. This report includes an appendix which presents

a costing of each proposal, or in some cases how much money a

proposal will raise. If you take all the reports proposals together there is of course an immediate net fiscal cost,

but like public investment this is not only money well spent, but is

likely to pay for itself because of the benefits to the economy that

will result.

[1] The relationship

between happiness, wellbeing and utility is both interesting and

complex, but that is for another time.

Source link